There is a prevailing tendency to assume that grandiose buildings like temples, colonnaded spaces, basilicas, bathhouses, and entertainment complexes were welcomed by inhabitants, but what if they were not?

Christopher Siwicki, research fellow at the Norwegian Institute in Rome, part of the University of Oslo, adresses this question in his research.

“Emperors and local politicians invested huge sums of money in improving the city. There was an idea that the grandeur of Rome should reflect the grandeur of the empire,” he says.

Siwicki is the first scholar to systematically explore the unpopularity and the damaging effects of monuments that are traditionally thought of as beneficial.

A city built on cities

Much of ancient Rome is still standing, particularly the area around Forum Romanum, a monumental construction that started growing in the early years of Rome in the valley between the Palatine Hill and the Capitoline Hill, two of the Seven Hills of Rome.

Every year millions of tourists visit both Forum Romanum and many other attractions, like the old temple of the Pantheon and the arena the Colosseum.

However, there is history also below ground. Siwicki describes Rome as a patchwork.

“Rome is a city built on former cities, and archeologists have been excavating Rome for 250 years. Still, there is a lot that we do not know. Some parts have been excavated, others not.”

Even The Norwegian Institute in Rome is hiding a treasure; a Roman watermill in the basement, part of the city’s former aquaduct system.

Two types of sources

In his research, Siwicki uses two types of sources. One is archeological evidence, examining the structures themselves and how they were incorporated into the existing urban fabric.This will involve charting the changes in urban land-use across multiple sites in Rome, and examining which buildings and places were replaced due to the construction of new monuments.

He considers using non-destructive archeological methods like ground penetrating radar to investigate what is beneath the antique structures.

The other sources are Greek and Latin texts from betwen 2nd century BC and 3rd century AD, which is the time period he studies.

Recorded speeches shed light on public opinion

An important written source is the Greek writer and philosopher Dio Chrysostom, who visited Rome and then returned to his Greek (today Turkish) city of Prusa. There, he tore down part of the city center in order to build a construction with a grandiose portico, which is a long, aisled hall with a colonnaded porch opening onto a public square.

Around 80 of Dio Chrysostom’s speeches have been preserved, and some of these were speeches to the people of Prusa. Five of the speeches are in defence of his construction project.

“We know from these speeches that he was critized enormously. In that way we get a glimpse, or more than a glimpse, that people cared about their city center,” Siwicki explains.

Prusa was part of the Roman empire, and what happened here ties in nicely with what happened in Rome, according to Siwicki.

An enorumous wealth gap allowed the rich to displace the poor

A lot of the money spent on magnificent constructions came from taxation. Furthermore, members of the elite gave gifts to the general population, such as buildings or gladiator games. In return, they got prestige, political power, and a lasting monument.

“If we think the wealth gap is bad today, it was enormous in ancient times. Some individuals and local politicians were close to billionaires,” Siwicki says.

Even if there are many unanswered questions, researchers know that magnificent buildings had negative consequences, also in Rome. The area around Forum Romanum was, for instance, for a long time a market and public meeting place, but as emperors and others started building temples, these activities were pushed away, according to Siwicki.

People were forced to move

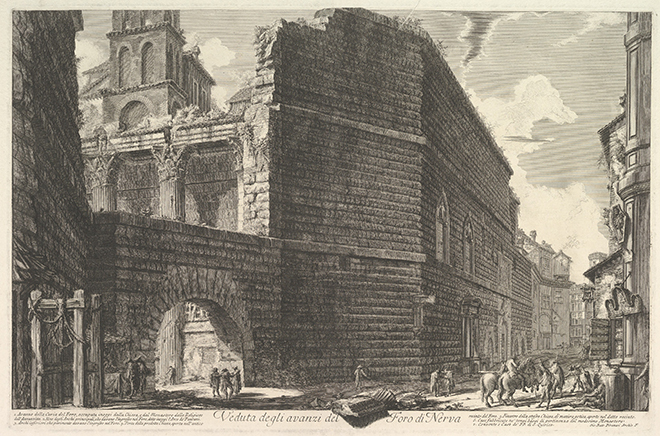

In the same area there are forums built by the dictator Julius Cæsar and emperor Augustus, who were in power slightly before and around year 0. These forums, which served as public spaces, demanded large areas in the center of Rome that until then had served as residental areas.

Many inhabitants were displaced in a city that was already overpopulated. Siwicki aims to investigate the consequences of these displacements.

A few ancient writers may give some hints. For instance, the Roman biographer Suetonius wrote that “Augustus made his forum narrower than he had planned, because he did not venture to eject the owners of the neighbouring houses”.

“We also know, from the Greek author Cassius Dio, that Cæsar was criticized for tearing down temples and peoples’ houses when he built a new theater,” Siwicki explains.

Around year 2 BC Augustus built a wall 30 meters high around his forum. The wall was meant to protect the forum from fires, however, it also destroyed roads and routes in the city. Some people got the gigantic wall as their closest neighbor.

“Augustus was praised for building the forum, but what about the people who were on the other side? When urban development happens, there are winners and losers,” Siwicki says.

We should learn from history

Many years have passed. Those who suffered injustice in Ancient Rome, have been dead for a long time. Still, Siwicki believes that it is important to explore this unknown part of history.

“Today’s understanding of history is shaped by writers and what we see. The writers belonged to the upper class, and the buildings that survived, belonged to the elite. If we are to understand what ancient Rome really was, we cannot just limit ourselves to what certain individuals said and did.”

Furthermore, he believes that these topics are relevant for cities of today. When buildings and areas are gentrified, meaning upgraded to increase attractiveness, some people fall behind.

“Creating and developing future cities is one of the biggest global challenges in this century. In some areas huge investments are being made, but it doesn’t mean that they are welcomed by all. Perhaps we can draw some lessons from history,” Siwicki says.