Cairo, January 2011. Thousands of young Egyptians demonstrated in Tahrir Square against the regime of President Hosni Mubarak. Smouldering discontent about corruption, the abuse of power and suppression which had started in Tunisia and spread to the rest of North Africa and the Middle East.

Jacob Høigilt, Associate Professor at the University of Oslo, travelled to Egypt in the wake of what later became the Arab Spring. He was at the time planning to study changes in the Arab written language.

“I was standing in a local bookshop in Cairo, searching for material, when I came across a shelf full of comic books,” Mr Høigilt recollects.

“They were funny, written in Arabic and quite clearly designed for adults. They struck me as being something entirely new and different.”

Publishing a book

This discovery sparked off a research project, which culminated in the end of 2018 with a book, entitled Comics in Contemporary Arab Culture: Politics, Language and Resistance (I.B. Tauris 2018).

In his book, Mr Høigilt introduces a new wave of so-called graphic novels – comic books for adults - written and published in Arabic.

"A few small comics groups had started to emerge just a few years before the Arab Spring,” he explains.

“But after 2011 there was a huge explosion in comic books for adults in this part of the world.”

For a long time, North American cartoonists such as Joe Sacco, Guy Delisle and Sarah Glidden have been drawing their impressions and experiences of the Middle East for a western public. However, as Mr Høigilt shows, the members of the new generation of Arabic cartoonists are keen to portray their societies and cultures from the inside.

“This wave is part of a broader cultural resurgence among young people who were involved in the prelude to the Arab Spring. At the same time the political and social opportunities which opened up after 2011 made it easier to start and create interest in such creative projects,” says Mr Høigilt.

National styles

Mr Høigilt started collecting all the comics he could find and he soon made contact with creative groups in Egypt, Lebanon, Tunisia and Morocco. While he was doing this the movement was growing.

He says: “Festivals like Cairocomics started up, along with an Arabic cartoon prize which is awarded each year in Lebanon.

As time went by he started to recognise the distinctive expressions and styles that separate the groups in the different countries.

“Egypt has its own school of cartoonists who have been keen to portray ordinary people and street life. They are usually funny and contain lots of sketches and slapstick humour. The Lebanese ones are much more highbrow and artistic,” he says.

Criticism of power and feminism

Comics for adults are not very old as a phenomenon. During the 1930s an international market developed, especially for American and Japanese cartoons for children. It was not until a few decades later that small, independent publishers started to publish comics designed for an older audience.

Containing humour, socially realistic depictions and an increasingly more critical slant on power structures, graphic novels for adults were born.

In his book Mr Høigilt picks out four topics which he believes are characteristic of the Arabic contributions to the genre:

“One of these is a very clear criticism of authoritarian, patriarchal structures. The emancipation of women and the problems associated with sexual relations are also prominent. Furthermore, one important function of comics is to provide young people with a voice in a society where they have previously been fairly marginalised in the public sphere.”

Resistance through language

The fourth and possibly the most important topic in his book is the language. Mr Høigilt says that he was initially fascinated by the fact that Arabic cartoons are written in dialects. Many of these have gradually been translated into English, French and Italian.

“Arabic is divided between high and low Arabic. Traditionally high Arabic has been a written language, while low Arabic is a colloquial language, used in everyday speech.”

Mr Høigilt explains that comics were an obvious example of wider trends in the Arabic world where writing the colloquial language was a way of breaking down formal social structures.

“This is connected to the resurgence of youth culture. When the written language becomes more informal, the threshold is also lowered, allowing young people to participate in the public debate.”

A window into youth culture

Comics can be used for entertainment purposes, but also for creating resistance. Consequently, Arabic cartoonists have sometimes been subjected to censorship.

“In Lebanon cartoonists and publishers who have criticised or lampooned religious leaders have been imprisoned and fined. And I believe that quite a few of the Egyptian comics which were published six or seven years ago would have been subjected to harsher treatment today,” says Mr Høigilt.

However, he believes that comics are not primarily valuable as expressions of political activism, but as socio-cultural and historical documents.

“Comic books serve as an important window into thoughts, feelings and trends in Arabic society. They can tell us a lot about the lives of young people in particular, in an exciting way which you don’t often gain access to in the Arabic media world.”

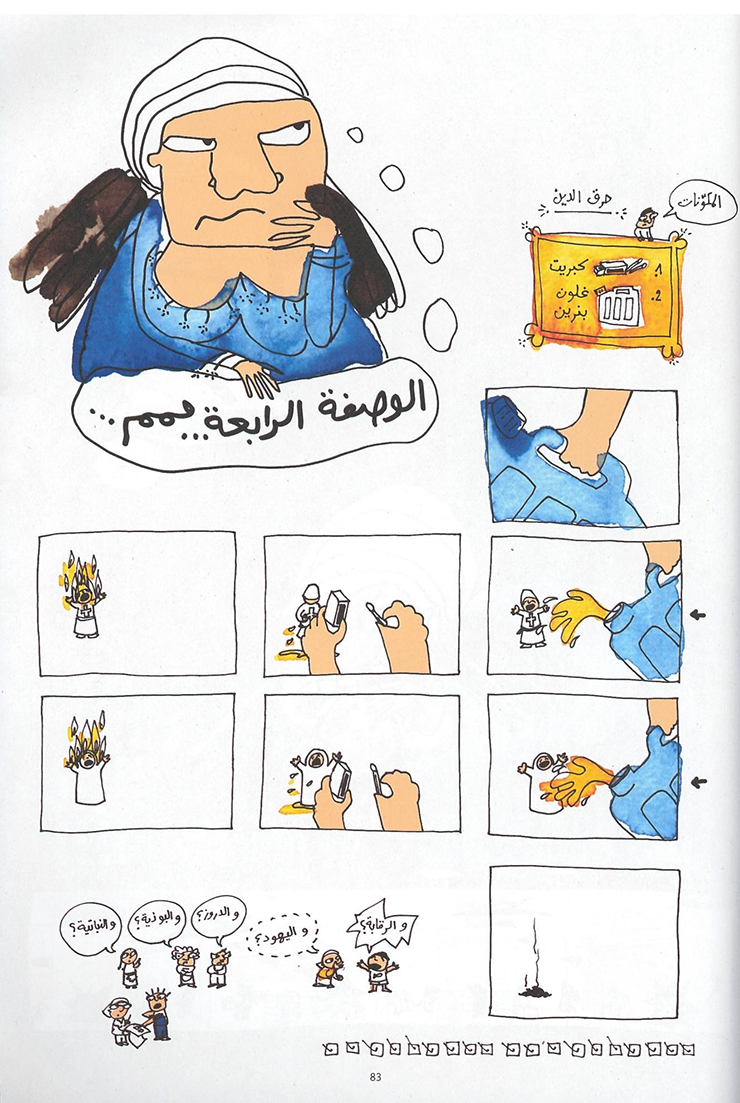

Photo caption strip: Page from Lena Merhej’s cartoon series entitled Lebanese Revenge Recipes (Samandal, no. 7, 2009). – This is a humorous take on Lebanese insults and oaths and shows how bizarre these are if they are taken literally. This page deals with the expression “May your religion burn”, and is a humorous approach to the inflamed topic of religion and politics in Lebanon. This story and another one about homosexuals in the same edition was the reason why a Lebanese political leader accused Samandal of blasphemy, hate speech, false news, and profanity. Amazingly the magazine was fined USD 20,000 in 2015,” says Mr Høigilt.

Photo caption traffic: – This caricature has been taken from the TokTok comic magazine (no. 11, 2014), created by Muhammad Shennawy, one of Egypt’s most prominent cartoonists. It was created after the Egyptian Revolution in 2011 and portrays a “parking assistant” (men who make a living from helping people to find parking places in the overcrowded streets of Cairo) helping a tank to find a vacant spot in the centre of the city. This drawing is subtle and smart because it humorously expresses the duplicity that exists in the relationship between ordinary Egyptians and the military: on one hand, you have “the people and the army”, while on the other you have “don’t believe that you are better than us”,” says Mr. Høigilt.

Jacob Høigilt is Associate Professor of Middle East studies at the University of Oslo. He is also Research Professor at the Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO). He has published the monograph Islamist Rhetoric: Language and Culture in Contemporary Egypt as well as in various edited collections and journals.

Høigilts is currently involved in the research project Journalism in struggles for democracy: media and polarization in the Middle East. The project is funded by the Research Council of Norway.