«Brokerage» is a key term in my ERC Starting Grant Project «Brokering China’s Extraversion: An Ethnographic Analysis of Transnational Arbitration». Preparing for my own Starting Grant interview a year ago, I encountered a number of brokers. Like many other candidates, I sought advice from people who knew two worlds – the world of EU funding and the world of academia – and were willing to help me bridge them.

Some claimed to possess exceptional insights into the purportedly mysterious decision-making in ERC scientific committees. Academic consultancy firms have a commercial interest in presenting the committees’ work as a black box that only they can give you a peek into.

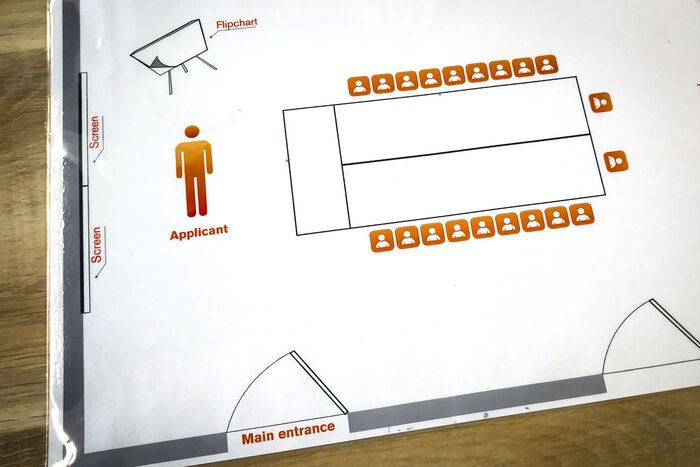

Others emphasized the random nature of decision-making in the committees and limited importance of the interviews. There were typically other academics, who didn’t think of themselves as brokers, but had gone through the ERC process and were willing to share their experiences. They had been in the cramped interview room, and helped me envision myself inside it (“there’s no place to put down your water bottle”; “regard the committee as fellow researchers: they’re visionaries, but also petty”).

In between the eager salespersons and conscripted volunteers were research officers at my university and the national level. They desired nothing more than for my application to succeed, and dished out a mix of encouragement and advice even as their uncertainty in my ability to make it sometimes was blatant.

My preparations included hours and days of procrastination and paralyzation. I searched around for advice even though I knew that focused preparation was what I needed the most. The list below is prepared with fellow applicants in mind.

- Speak with contagious enthusiasm. You are addressing to fellow researchers. They think research is awesome, but they are also tired, hungry, nervous, and/or distracted. Make them forget this as they get excited about the prospects of funding your project.

- Provide short replies. Around twenty of your peers will evaluate you, and many have prepared questions based on your application. Give them the opportunity to pose these questions by offering short answers.

- Provide concise replies. Most of the questions I got could be anticipated. Yet, I did not have adequate answers at hand during early trial interviews or conversations. The most important preparation I did was to prepare concise replies and straightforward examples in response to key questions. Some questions were broad enough to structure academic articles after the project was funded. No researcher is impressed by an answer that mostly conveys that “it’s complicated.”

- Prepare a Q&A list. This relates to the two previous points. I found it helpful to write out the questions and my answers, often in bullet points. I practiced presenting the answers in order not to find myself lost in a line of reasoning that I regretted having started during the interview. By the time I went to Brussels, the list was internalized and the physical document was destroyed.

- Take special care to reply adequately to the first interviewer. This person knows your application and the external experts’ opinions the best, and will ask questions based on this information. The advice to remain concise is still relevant, and relatively short answers can be followed by indications that you’re happy to elaborate in the direction the interviewer deems useful (eg. “did that address your concern?”).

- If you anticipate a difficult question, acknowledge the challenge. ERC projects are supposed to entail risks. When committee members bring up a risk you have anticipated, you have communicated the relationship between risks and gains well. Acknowledge the challenges in your project, and provide well-prepared answers to explain why you are well-equipped to deal with them and how you plan to do it.

- Treat negative committee members as if they are genuinely curious. If an adverse attitude shines through, handle it with grace and earnestness. If you react defensively, other committee members may pick up on your negative body language or tone and become more critical towards you even if the criticism raised is unfounded.

- Make those asking the questions feel respected and intelligent. The committee members too are in front of their peers. Sometimes a question will come across as misplaced. A reflection that’s related to the question may put both the person asking and yourself in a better light than digging for clarifications.

- Start addressing key challenges in your presentation. It’s tempting to hope that the committee will overlook the key challenges in the proposal. It’s also unlikely. By bringing up the main one(s) in your presentation, you can start address some of the questions the committee members will have during the Q&A. To convince the committee that you don’t have blind spots, your replies are strengthened when they refer back to the presentation as well as the application.

- Time and test your presentation. Timing is simple. Just do it. There are many things applicants can’t control, but everyone can keep within the designated time. Test the presentation on colleagues, fellow applicants, research officers, or friends. Invite questions. Take critique seriously. A good research article requires formal and informal peer review, critical comments, painful choices, and numerous drafts. So does an 8-minute presentation of a 1.5 Million Euro research project.

- Wear clothes you’re comfortable in. If you don’t wear blazers, don’t buy one for this occasion. If a suit makes you feel like an awkward teenager, there are other options. If you feel great in a tie, pull out your favorite one, even if your university’s research officer says it’s way too flashy. To present the best version of your researcher self, it helps to feel like yourself.

- Have a waiting room strategy. You have to wait for an hour alongside other candidates. The atmosphere in the room can be tense—or very congenial. Be prepared for both, and decide whether you want to shut the world out by wearing headsets or get warmed up through small talk with fellow candidates. (If you go for the latter, be ready for annoyed glances from cramming candidates.)

- Have a strategy for entering and exiting from the interview room. If you’ve never felt like a deer in headlight, skip this point. For me, it helped to envision the first 30 seconds of the interview: I would shake the hand of the committee leader, look at him, look at a section of the people in the room, and say “Thank you for this opportunity.” “Good morning” or “I’m glad to be here” would have worked just as well, but having the sentence ready helped me get on the right track before the presentation. I didn’t have a strategy for exiting from the interview room. When the clock suddenly beeped in the middle of my answer, I kept on finishing replying as the secretary dragged me out of the room. Stopping mid-sentence to say a calm “thank you” would have made for a more dignified sortie.

- Present a compelling vision for future work. The list has gone full circle: You have great ambitions, you have done solid research in the past that enables you to realize these ambitions, and all you need is the funding from the ERC to get on with it. Be prepared to convince the committee of this during your designated 20 minutes.