The Power of ✨Pan-East Asian Soft Masculinity✨

POV: you’re tasked to compile a reading list of at least 600 pages of relevant academic literature on your chosen topic and make a critical summary 👁👄👁

Pan-East Asian soft masculinity. That’s a lengthy word – what exactly is it? You may or may not have noticed it, but it has gradually emerged into the global mainstream for the past years. Maybe the Korean boy band, BTS rings a bell? Or maybe you have browsed through Netflix and effortlessly observed covers of Asian TV shows with young, handsome yet gentle looking fellows? In that case, those are examples of pan-East Asian soft masculinity. At face value, this phenomenon may be seen as a mere aesthetic or a temporarily trend, but for some it’s considered as something more profound – for better or worse. That being said, although “pan-East Asian soft masculinity” implies a form of transnational uniformity between East Asian countries (typically China, Japan, and South Korea), it affects each country differently – thus offers a myriad of intriguing aspects to delve into!

The makeup of this soft masculinity is majorly influenced by the aesthetics of the genre Boy’s Love (BL) which portrays feminized, beautiful men situated in a, sometimes hinted, sometimes obvious, homosexual relationship. Considering this feminized masculinity affiliated with non-heteronormative practices, one may suggest that this widespread pan-East Asian soft masculinity perhaps catches enough people’s attention to stir the traditional gender and sexual norms. However, there are currently few empirical studies that can back up this assertion. Or more specifically, in order to get empiric, “solid” evidence to validate this, we would have to first narrow down the search field. By a lot. This blog post may contribute to take a further step towards this direction by summarizing my research on existing academic literature relevant to the following, slightly more narrowed down, question:

How may the danmei aesthetics influence the idea(l) of Chinese masculinity in contemporary China?

Catching pan-East Asian soft masculinity in 4K📸

Danmei 耽美 (indulging beauty) is the Chinese version of BL. To illustrate what the danmei aesthetics entails and to demonstrate how its soft masculinity takes part in the bigger picture of China, let’s use the acclaimed BL-story, Mo Dao Zu Shi 魔道祖师 (Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation) by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu 墨香铜臭, as an example. A crucial premise to remember when talking about this is that danmei creations come in different size and shapes. In fact, this is a paramount for allowing danmei to circumvent the opposing heteropatriarchal Chinese state discourse. Correspondingly, the original shape of Mo Dao Zu Shi is a web novel with explicit homosexual content, but there are also successful adaptations such as the live-action web drama, The Untamed (2019) and the original net animation Mo Dao Zu Shi (2018) by which the homosexual depiction in both series are downplayed quite significantly.

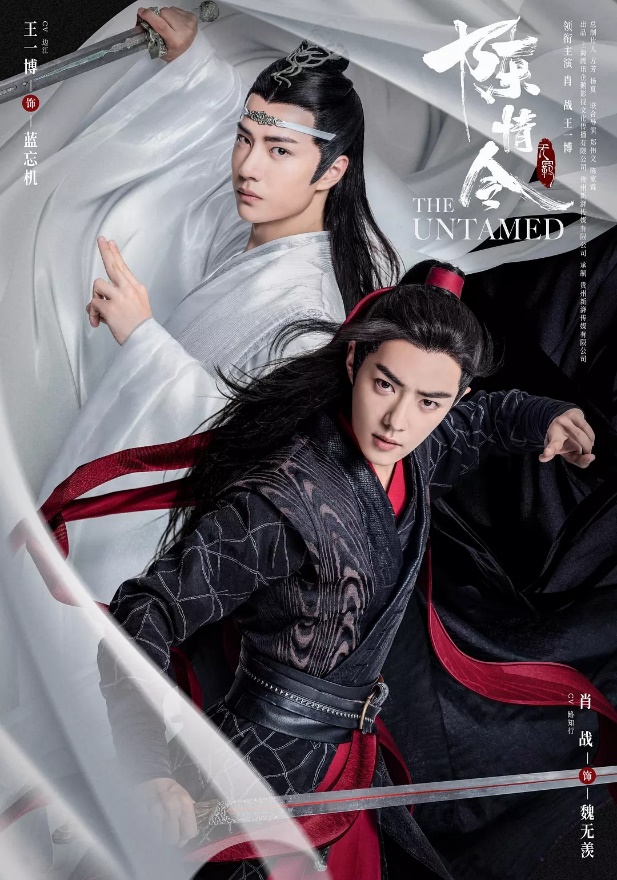

Figure 1. Lan Wangji 蓝忘机played by Wang Yibo 王一博 (left) and Wei Wuxian 魏无羡 played by Xiao Zhan肖战 (right) in the live-action adaptation, The Untamed (2019). Retrieved 02. april 2024, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt10554898/mediaviewer/rm3452804353?ref_=ext_shr_lnk

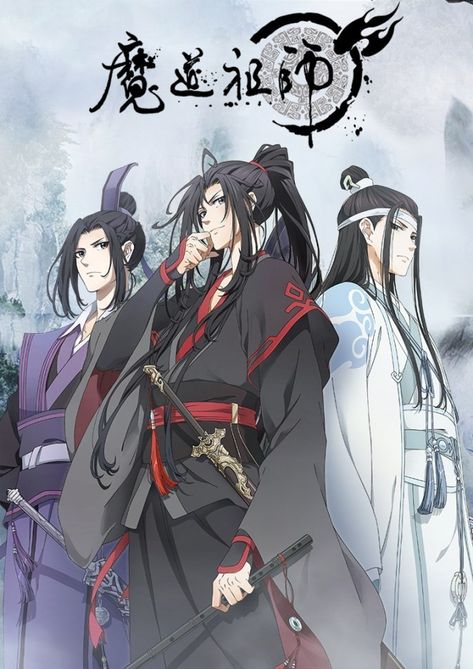

Figure 2. The animated adaptation, Mo Dao Zu Shi (2018). Retrieved 28 November 2022 from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt9005728/?ref_=tt_mv_close

As illustrated by these posters and suggested by the literal meaning of danmei (indulging beauty), men are the center point and rendered with an aesthetic that romanticizes their relationships with other men. According to studies, physical acts in danmei stories are often (but certainly not always) glossed over, while metaphors, euphemisms, and aesthetically rendered details of the setting, costume, and male body carry the narration. Meaning, the indulged beauty in danmei may be created through not only aesthetic visuals, but also through a narrative of male-male sexual behavior expressed in a “purified” and “sublime” fashion. Consequently, the generated pleasures of danmei lies in the appreciation of the danmei aesthetics, creating a space for pleasure-seeking adventures and fantasizing for the consumer of danmei – who, by the way, typically are heterosexual young women.

That said, remember that danmei creations come in different size and shapes – and for different reasons. It is in many ways a gift and a curse. On one hand, it allows for a variety of pleasure-driven preferences for the danmei consumers. On the other, it’s an imposed strategic choice by danmei creators to prevent possible demolishment by the Chinese state. Another aspect to add, is the commercialization of danmei aesthetics which aligns with the women-oriented market culture under the “she-economy” that recruits men possessing the pan-East Asian soft masculinity. In China, these men are known as xiao xian rou 小鲜肉 (little fresh meat) and are characterized by delicate, groomed, and effeminate appearance. In fact, the actors of The Untamed were carefully selected to accommodate the danmei aesthetics.

To further illustrate, the largest sponsor for the Mo Dao Zu Shi animated adaptation, namely Cornetto, incorporates their Chinese brand name, ke’ai duo 可爱多 (Much Cuter), as a tagline for the animation series. Furthermore, not only does it appeal to the audience with the youthful and soft masculinities of the characters, but also, by bringing reality (physical products that can be bought in real life) into the fictional world, creates a sense of closeness between fiction, reality and the brand. In the commercial break in episode two, one of the main characters, Lan Wangji is presented as the “blue friend” and endorser of Cornetto. This actualizes a relation between the danmei audience (and potentially Cornetto consumer) and the fictional character, inviting an appreciation of danmei aesthetics on a more personal level.

Figure 3. One of the main characters, Lan (literally “blue” in Chinese) Wangji, advertising Cornetto’s “blue friend” ice cream. Retrieved 28 November 2022, from https://www.sohu.com/a/242423098_100132682

Another example is the inherently “meta” commercial break by Unified Instant Noodle in the live-action adaptation. The actor, or “little fresh meat”, Wang Yibo who plays Lan Wangji demonstrates the interconnected ways of commercializing pan-East Asian soft masculinity. In the advertisement, Lan Wangji is introduced to a cup-ramen depicted with the animated character of Wei Wuxian. This “self-referential” element cleverly contributes to expand the recipient group by appealing to fans of different mediums (animation vs live-action) that displays this soft masculinity. These two examples only scratch the surface of how the market culture uses the visual and narrative pleasure-generating danmei aesthetics for all it is worth. “Little fresh meat” usually serves as official brand ambassador for products and businesses ranging from high-end cosmetic brands to fast-food outlets in order to please the eyes of the women and young consumers.

Figure 4. Screenshots taken from the commercial break by Unified Instant Noodle in the live-action adaptation, The Untamed. Retrieved 28 November 2022, from https://v.qq.com/x/page/c0031s7crtn.html

Little fresh meat doesn’t fully pass the Chinese state’s vibe check🚫🙅🏻♂️

Despite the increasing visibility of pan-East Asian soft masculinity and its commercial driving force, it is worth to note that the more profound consideration and appreciation of danmei aesthetics is practiced, first and foremost, within the danmei subculture. In other words, it doesn’t have a dominating place in society, and thus it doesn’t really constitute an immediate threat or challenge to Chinese state discourse and its male-dominated mainstream gender order that upholds the male ideal of versatile, successful, upper-middle-class manhood which conforms to the heteropatriarchal model of love and marriage.

That said, danmei aesthetics has taken part in generating concerns, or a “sissyphobic” discourse by which government officials have alerted to a “crisis of masculinity”. This has led to tension and the competing of different masculinity discourse. The main regulator to this competition is the National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA) which is primarily responsible to oversee media content in China and to implement the Chinese state’s propagandist strategies that embrace heteronormative reworkings of Chinese traditionalism. This traditionalism favors traditional family unit and services of societal and national-level goals. Although China has a long-documented history of homosexual practices and relationships, by which in some cases the effeminate man was seen as the ideal male, in 2021, NRTA ordered to firmly put an end to “abnormal aesthetics such as sissy men”. This might be explained by Chinese state’s conception of these historical and traditional non-heteronormative practices as “outdated” and contradictory to the image of contemporary China that the state wishes to display.

According to Chinese state discourse, the inner quality of a man is his degree of cultural cultivation and his patriotic sentiment, which weighs much more than his appearance. Furthermore, the state’s idea(l) of masculinity is defined by political loyalty to the state, adherence to Confucian values such as homosocial brotherhood, and a rejection of femininity and queerness. Scholars suggest that this kind of gender norm is intertwined with the rising of nationalist sentiments: on the one hand, the gender norm is driven by the state’s desire to expand the consumer market by allowing women and the young to affectively consume “little fresh meat”, while on the other hand, strengthen ideological education. Clearly, the state considers the pros and cons of making use of pan-East Asian soft masculinity, as it’s not only the masculinity that is soft, but also the power it holds – a soft power (🥁pun intended). As such, how Chinese men look, behave, and are represented has become a topic of heated debates in public discourse.

The wen-wu construct🧘🏻♂️🧠🔄🥋💪🏻

Amidst unpacking the essence of the soft masculinity of danmei aesthetics, one may ask: is it really that sensationally contradictive? Considering the aesthetical aspect of this question and by putting it into the Chinese context, the simple answer is: no, not that much. But also, yes.

To understand the idea of Chinese masculinity, we have to understand the wen-wu construct. This construct helps to generalize the evolving concepts, icons, and symbols of Chinese masculinity. Wen 文, refers to the mental, civil and cultural accomplishment by the typical talented scholar, while wu 武, refers to the physical and martial attainments by the typical soldier. The essence of the wen-wu construct is very similar to the well-known balancing between yin 阴 (e.g., female) and yang 阳 (e.g., male). However, unlike yin-yang, the wen-wu construct is exclusively used to describe Chinese men. This is because the construct is founded on the traditional Confucian gender order that legitimized and naturalized the imbalance in power between the sexes in ancient China. Interestingly enough though, it may be applied to women, but only when they have transformed themselves into a man – like in the story of Mulan. As such, the wen-wu construct follows the logic of gender being a cultural constructed role – a gender performativity, to use a more popular term of it. Anyhow, the wen-wu construct reflects the reality of the Chinese imperial times when wen held primacy over wu by more commonly passing the civil examination system that was the decisive factor to distribute power in the society. However, today, the wu ideal has achieved increased prominence throughout Chinese history whereby the state has made an effort to promote the peasant or working-class hero, and more recently images of masculinity from the West. Nevertheless, this historical and cultural rootedness of male effeminacy and scholar-type masculinity in Chinese culture of Confucian tradition has perhaps made the bodily rhetoric of danmei aesthetics be perceived by the Chinese state as less subversive for their discourse and hegemonic gender order.

In fact, the wen-wu construct is based on the idea that a man is made up of both the mental and refined qualities of wen and physical and military qualities of wu, in which both biology and culture plays a role in shaping the ideal man. Therefore, in principle, a scholar is no less masculine than a soldier. Indeed, at certain points in history the expectations of the ideal man would change and be expected to embody a balance of wen and wu, or only one or the other – either way was considered acceptably manly, since wen and wu in their own right are specific qualities of the male. In other words, the idea of masculinity stays based on the wen-wu construct and its function to identify and order human relationships. However, the ideal of Chinese masculinity – or more simply put, the wished ratio between wen and wu – changes along with the development of the society.

The current phenomenon of pan-East Asian soft masculinity has indeed made us reconsider one’s perspective on masculinity. However, by glancing backwards in time, we can see that the idea of the beautiful man existed in both China and Japan in traditional times. The appreciation of beautiful men was very common among the elite male culture in Ming-Qing China around the 17th century. In the 20th century, this appreciation went beyond the elite male culture, partly thanks to the popularity of manga and the rise of cultural studies.

Today, danmei aesthetic which entails emphasis on cultivated visuals and intimate relationships creates certain modes of appearance and behavior that may have an effect that reaches out and beyond the realm of danmei subculture. In fact, according to studies, groups of young men in East Asia are already performing this soft masculinity to resist and subvert traditional patriarchy and homophobia, and as a solidarity-building activity. Cuteness and femininity are therefore attributes that men may also want. This leads to questions about the sexuality of the young men who pursue such an aesthetic, in which a study found that some men assume that this type of male appearance is indeed heterosexually appealing – which conforms with the fact that danmei aesthetics is much shaped by and for heterosexual women. This may raise new questions about how homosexuals feel about heterosexual women projecting their fantasies through a romanticized and homosexual lens.

TL;DR: how the tables have turned 💰🧏🏻♀️👧🏻

The popularity of pan-East Asian soft masculinity features a new type of male beauty sparked by a transnational flow of aesthetics, promoted by a commercial drive, and targeted primarily at heterosexual women and young fans. Although this embedded danmei aesthetic contradicts the Chinese state’s discourse of masculinity, danmei creations have the tendency to (unconsciously and consciously) comply with current traditional gender and sexual norms in contemporary China, thus persevering the dominant heteropatriarchal ideal of masculinity. The other more sexually graphic forms of danmei aesthetics are not suppressed by Chinese state discourse simply because of explicitly sexual material, but also because it is a part of the bigger picture of China that the Chinese state wants to frame through firm propagation of party-line moral-political discourses.

By using the wen-wu construct, pan-East Asian soft masculinity may be understood as a restructured ideal that still exhibits essential elements of wen-wu, but is more mindful of women and therefore has “softened” and become more “feminine”. However, the key here is not to focus on what’s new about this new male ideal of soft masculinity, but to look at who are the ones changing the ideal. In the women-oriented consumer culture in China, the ones with the power to change discourse rests with the consumers, who are women and the young of increased buying power. 🎤-drop.

References

Baecker, A., & Hao, Y. (2021). Fan labour and the rise of boys' love TV drama in China. East Asia Forum Quarterly, 17-20.

Butler, J. (1993). Imitation and Gender Insubordination. In J. Butler, H. Abelove, M. A. Barale, & D. M. Halperin (Eds.), The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader (pp. 307-320). London: Routledge.

Cao, S. (2022). Cultivating shenti in everyday life: Self, relationality and embodied masculinity in China. The Sociological Review, 438-454.

Chang, J., & Tian, H. (2020). Girl power in boy love: Yaoi, online female counterculture, and digital feminism in China. Feminist Media Studies, 604-620.

Fang, K., & Repnikova, M. (2018). Demystifying “Little Pink”: The creation and evolution of a gendered label for nationalistic activists in China. new media & society, 2162-2185.

Feng, D. W., & Yu, M. H. (2022). Tradition, modernity, and Chinese masculinity: The multimodal construction of ideal manhood in a reality dating show. Pragmatics, 191-217.

Feng, J. (2009). "Addicted to Beauty": Consuming and Producing Web-based Chinese Danmei Fiction at Jinjiang. Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, 1-41.

Fung, A., Pun, B., & Mori, Y. (2019). Reading border-crossing Japanese comics/anime in China: Cultural consumption, fandom, and imagination. Global media and China, 125-137.

Heng, Y.-K. (2010). Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the softest of them all? Evaluating Japanese and Chinese strategies in the ‘soft’ power competition era. International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, 275-304.

Heng, Y.-K. (2014). Beyond ‘kawaii’ pop culture: Japan’s normative soft power as global trouble-shooter. The Pacific Review, 169-192.

Hernandez, A. D., & Hirai, T. (2015). The Reception of Japanese Animation and its Determinants in Taiwan, South Korea and China. animation: an interdisciplinary journal, 154-169.

Hu, L. (2018). Is masculinity ‘deteriorating’ in China? Changes of masculinity representation in Chinese film posters from 1951 to 2016. Journal of Gender Studies, 335-346.

Huat, C. B. (2004). Conceptualizing an East Asian popular culture. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 200-221.

Ishii, K. (2013). Nationalism and preferences for domestic and foreign animation programmes in China. the International Communication Gazette, 225–245.

Iwabuchi, K., Berry, C., & Tsai, E. (2017). Routledge Handbook of East Asian Popular Culture. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Jankowiak, W., & Li, X. (2014). The Decline of the Chauvinistic Model of Chinese Masculinity: A Research Report. Chinese Sociological Review, 3-18.

Jung, S. (2009). The Shared Imagination of Bishonen, Pan-East Asian Soft Masculinity: Reading DBSK, Youtube.com and Transcultural New Media Consumption. Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, 20.

Leonard, S. (2005). Progress against the law: Anime and fandom, with the key to the globalization of culture. INTERNATIONAL journal of CULTURAL studies, 281-305.

Li, X. (2020). How powerful is the female gaze? The implication of using male celebrities for promoting female cosmetics in China. Global Media and China, 5, 55-68.

Lin, Q. (2021). "Nisu" Culture in Chinese Fandom Under the Rise of Female Gaze -- A Word of Honor (2021) Case Study. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 229-236.

Louie, K. (2002). Theorising Chinese masculinity : society and gender in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Louie, K. (2012). Popular Culture and Masculinity Ideals in East Asia, with Special Reference to China. The Journal of Asian Studies, 929-943.

Louie, K. (2015). Chinese Masculinities in a Globalizing World. London: Routledge.

Louie, K. (2017). Asian Masculinity Studies in the West: From Minority Status to Soft Power. Asia Pacific Perspectives v15n1, 1-15.

Luo, W. (2017). Television’s “Leftover” Bachelors and Hegemonic Masculinity in Postsocialist China. Women's Studies in Communication, 190-211.

Martin, F. (2017). Queer Pop Culture in the Sinophone Mediasphere. In K. Iwabuchi, C. Berry, & E. Tsai, Routledge Handbook of East Asian Popular Culture (pp. 191-201). London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Meyer, U. (2013). Drawing from the body – the self, the gaze and the other in Boys' Love manga. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 64-81.

National Radio and Television Administration 国家广播电. (2021, September 2). Guojia guangbo dianshi zongju bangong ting guangyu jinbu jiaqiang wenyi jiemu ji qi renyuan guanli de tongzhi [Notice on Emphasizing the Management and Regulation of Entertainment Programs and Related Personnel]. Retrieved from National Radio and Television Administration 国家广播电: http://www.nrta.gov.cn/art/2021/9/2/art_113_57756.html?fbclid=IwAR1yzPVvtRxes-ZjUg0j96qMXYqNad509eBHR_vAMHAjGAgkuuIxr-oKD3Y

Ng, E., & Li, X. (2020). A queer “socialist brotherhood”: the Guardian web series, boys’ love fandom, and the Chinese state. Feminist Media Studies, 479-495.

O’Neill, R. (2015). Whither Critical Masculinity Studies? Notes on Inclusive Masculinity Theory, Postfeminism, and Sexual Politics. Men and Masculinities, 100-120.

Saito, A. P. (2017). Moe and Internet Memes: The Resistance and Accommodation of Japanese Popular Culture in China. Cultural Studies Review, 136-150.

Song, G. (2022). “Little Fresh Meat”: The Politics of Sissiness and Sissyphobia in Contemporary China. Men and Masculinities, 68-86.

Tencent. (2019, August 5). Wuxian suan shuang, chenqing yi xia 无羡酸爽,陈情一夏. Retrieved November 24, 2022, from Tencent: https://v.qq.com/x/page/c0031s7crtn.html

Tian, X. (2020). Homosexualizing “Boys Love” in China: Reflexivity, Genre Transformation, and Cultural Interaction. Prism, 104-126.

Wang, A. (2021). NONNORMATIVE MASCULINITY IN DANMEI LITERATURE: ‘MAIDEN SEME’ AND SAJIAO. Moment Dergi, 106-123.

Wang, S. (2020). Chinese gay men pursuing online fame: erotic reputation and internet celebrity economies. Feminist Media Studies, 548-564.

Wang, Y., Mao, L. L., & Smith, A. B. (2022). Appraisal and coping with sport identity and associatied threats: exploring Chinese fans reactions to "little fresh meat" in NBA advertisements. European Sport Management Quarterly, 1-22.

Wen, H. (2021). Gentle yet Manly: Xiao xian rou, Male Cosmetic Surgery and Neoliberal Consumer Culture in China. Asian Studies Review, 253-271.

Wu, Y., Alleva, J. M., & Mulkens, S. (2020). Factor Analysis and Psychometric Properties of the Chinese Translation of the Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale. Elsevier, 244-256.

Xu, Y. (Producer), Liang, S., Liu, X., Zhu, K. (Writers), & Xiong, K. (Director). (2018). Mo Dao Zu Shi di 02 hua 魔道祖师 第02话 [The Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation Chapter 02] [Motion Picture]. Retrieved November 24, 2022, from https://v.qq.com/x/cover/k4mutekomtrdbux/a0026fo0kg8.html

Yang, F. (2020). Post-feminism and Chick Flicks in China: Subjects, Discursive Origin and New Gender Norms. Feminist Media Studies, 1-16. doi:10.1080/14680777.2020.1791928

Yu, Y., & Sui, H. (2022). The anxiety over soft masculinity: a critical discourse analysis of the “prevention of feminisation of male teenagers” debate in the Chinese-language news media. Feminist Media Studies, 1-14.

Zhang, C. (2016). Loving Boys Twice as Much: Chinese Women’s Paradoxical Fandom of “Boys’ Love” Fiction. Women's Studies in Communication, 249-267.

Zhang, L. 张. (2019). "Dongman IP+ pinpai" de zhenghe yingxiao chuanbo 动漫 IP+ 品牌”的整合营销传播 [Integrated Marketing Communication of “Anime IP + Brand”]. China Venture Capital, 143-144.

Zhang, Q., & Negus, K. (2020). East Asian pop music idol production and the emergence of data fandom in China. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 493–511.

Zhao, J. J. (2016). A splendid Chinese queer TV? "Crafting" non-normative masculinities in formatted Chinese reality TV shows. Feminist Media Studies, 164-168.

Zhao, J. J. (2021). Introduction: global queer fandoms of Asian media and celebrities. Feminist Media Studies, 1028-1032.

Zheng, T. (2015). Masculinity in crisis: effeminate men, loss of manhood, and the nation-state in postsocialist China. Etnográfica, 347-365.

Zheng, X. (2019). Survival and migration patterns of Chinese online media fandoms. Transformative works and cultures, 30. doi:10.3983/twc.2019.1805

Zhu, G., Zhang, A., Cheng, L., Shi, K., & Wang, Y. (2022). “Saving Our Boys!”: Do Chinese Boys Have a Masculinity Crisis? ECNU Review of Education, 1-11.

Zsila, Á., & Demetrovics, Z. (2017). The boys’ love phenomenon: A literature review. Journal of Popular Romance Studies, 1-16.

Sofie Balstad completed her undergraduate studies in Chinese language and China studies, and her master’s studies in Chinese culture and society at the University of Oslo, and is currently a master’s student in Screen Cultures. Her academic interests revolve around East Asian pop culture, digital media culture and soft power – and what implications these factors combined may have on the societal and individual level.