A city that created history

It was actually in Shanghai that the negotiation originally started. However, it soon came to a deadlock. In the face of the two sides’ substantial divergence, Zhou Enlai proposed that the negotiation be shifted to Hangzhou. The change of places had a really magical effect and the breakthrough soon took place in Hangzhou, near the West Lake. In fact, when Edward Cox, the President Nixon’s son-in-law, recalled this story afterwards, he commented that the Communiqué should indeed be called “Hangzhou Communiqué” [1]. Shortly after the critical juncture of 1972, the Chinese city further welcomed other renowned international guests like the then French President Georges Pompidou.

The “Geneva of the East”

As a matter of fact, early in the 1950s, Hangzhou was already planned as an internationally opened city. In the 60s city plan, one could even find international conference halls, international science, technology, and culture centers, and international hotels in future Hangzhou on the waterfront of the West Lake [2]. In the actual city construction, factories were being moved out of the city, and natural scenery and cultural relics were specifically preserved [3]. Given P.R.C.’s then relatively isolated international status, as well as industrialization as its chief urban development strategy, it is really hard to imagine all these that had happened in a 50s and 60s Chinese city. Yet they were all real. In the past few decades, the plan, as well as its implementation, has long been mentioned and talked about by Hangzhou locals, with its remarkable name – the “Geneva of the East” (dongfang rineiwa), that is, to build future Hangzhou as a cosmopolitan city like Geneva.

According to the available sources, the conception was in high likelihood shaped by the experience of the 1954 Geneva Conference, in which the P.R.C. was, for the first time, present in a global diplomatic arena and played an influential peace-keeping role. Shortly after that onference, the then premier and foreign minister Zhou Enlai visited Hangzhou, and the planning of this city was directed accordingly towards building it into an international conference city, which would be like Geneva in Switzerland [4].

Beyond the city plan - a political plan

Before a further interpretation of the plan, it is also meaningful to consider Hangzhou’s special political status in the early P.R.C. Probably because of its remarkable natural

and cultural environment, the city was then the very place of informal politics that Mao Zedong, for instance, had visited over 40 times during 1953-76 and called the “second

home” [5]. It has been a place that has witnessed several crucial moments of the P.R.C. history, like the drafting of the state’s first constitution in 1954, as well as Nixon’s 1972

visit and the bilateral agreement on the communiqué. Actually, planning for a “Geneva of the East” has often been mentioned by locals and also officials as a direct decision of

the national leaders like Zhou Enlai and even Mao Zedong [6]. Against this background, the city planning naturally had political implications. Arguably, it was never only city planning of Hangzhou, but also political planning in Hangzhou. At the local levels, the “Geneva of the East” meant a city plan under significant central directives; at the

central level, it should involve a political plan of the young P.R.C.’s future!

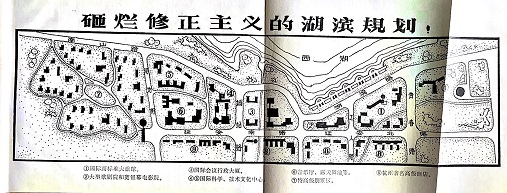

How was the future conceived in the plan, then? While having laid great value on this plan, observers like historian James Z. Gao have additionally noticed the influence of Soviet advisors on Hangzhou’s city planning in the early 1950s [7]. Nevertheless, no evidence has indicated any impact of the later Sino-Soviet Split upon the city plan and its implementation. By contrast, it was during the Cultural Revolution that the plan incurred many local criticisms, for having then been considered too “revisionist” and “capitalist” [8]. Most saliently, the plan was named the “Geneva of the East,” rather than a type of “St. Petersburg of the East” or the “New York of the East” (which was interestingly another vision of future Hangzhou in the Republican era). As a political plan, it neither followed the Soviet model, nor the American one during the cold war. Arguably, China’s decision makers were then conceiving a more independent development path “with Chinese characteristics” [9].

Photo: Smashing the “Geneva of the East,” published during the Cultural Revolution.

Notes: (1) High-standard international grand hotels, (2) large opera and widescreen

cinema, (3) international conference and administrative halls, (4)(5) international

science, technology, and culture centers, (6) concert halls and dance floors etc., (7)

area of exceptionally high-grade villas, (8) famous high-grade stores in Hangzhou.

A prominent feature of this neither-Soviet-nor-American development path was its vision of China’s internationalization. Again, according to the plan, there would be numerous international conferences plus other international scientific, cultural, art, and economic activities in future Hangzhou; the Chinese city would function then as a significant node of world peace and development, like Geneva in Switzerland. As the plan envisioned that China would return to the world family with such a neutral status, the major consideration behind the planning scheme may have included the reluctance to be hijacked by either camp of the cold war.

Contemporary story of the city and the country

This unusual episode of history has been revisited by a research group in Hangzhou, of which the author is the project director. During the G20 Hangzhou summit in 2016, questions like “why Hangzhou?” emerged in the Chinese media, as the city was chosen as the host of such a significant global conference. Some have referred to the U.S.-China negotiations that occurred in Hangzhou in 1972 as a possible reason why the G20 summit was located in Hangzhou in 2016 rather than larger cities like Beijing or Shanghai [10]. Along with this process, the “Geneva of the East Plan” was again brought to the attention of the general public.

The past apparently did not just pass by so simply. It has left observable influence on the present. At the city level, Hangzhou’s contemporary city plans have inherited the past plans in the 1950s and 60s. The “Geneva of the East” is still being talked about, and there have indeed been numerous international conferences, e.g. the 2016 G20 summit in today’s Hangzhou. At the national level, the later reform and opening was obviously not an abrupt decision, in view of the previous political plan of an independent but not isolated development path “with Chinese characteristics.” In retrospect, the reform and opening seems just like an approach to actualizing the previous conception and the achievement is exceptional and easily perceivable. In this way, it is also a wonder to see such a parallel transformation of a city and of a country. Back to the cold war condition over a half century ago, one could hardly imagine how aspiring and daring the formulation the “Geneva of the East” was both as a city plan and as a political plan. Given the noteworthy connection of the past and the present, the rediscovery of future planning in early P.R.C. Hangzhou indeed opened up a brand new perspective for observing contemporary China. One may even argue that the “Geneva of the East,” conceivably an unusual legacy of the past, could now serve as a “Geneva” code of the “P.R.C. enigma”!

Photo: http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_46506cd40102wmm7.html.

References and notes

April 22, 2012. It is now often called “Shanghai Communiqué,” because it was announced in Shanghai.

[2] Liu Deke 刘德科, “1967-1978: chengshi jingshen de quzhe zhi lu [1967-1978:城市精神的曲折之路 1967-1978: Meanderings of the City Spirit],”

Hangzhou Ribao, September 10, 2009.

[3] Zhejiang sheng jiben jianshe dou pi gai lianluozhan deng [浙江省基本建设斗批改联络站等 The Liaison Office for Struggling, Criticizing,

and Reforming [at the Front of] Capital Construction in Zhejiang Province etc.], Zalan “dongfang rineiwa” [砸烂“东方日内瓦” Smashing the “Geneva of the East”]

(Hangzhou: 1968), 15.

[4] Yu Senwen 余森文, “Hangzhou yuanlin jianshe de huigu [杭州园林建设的回顾 A Review of Park Construction in Hangzhou],” in Xihu fengjing yuanlin (1949-1989)

[西湖风景园林(1949-1989) The Scenery and Parks of West Lake (1949-1989)], edited by Hangzhoushi Yuanlin Wenwu Guanliju [杭州市园林文物管理局

Hangzhou Municipal Bureau of Landscape and Cultural Relics Management] (Shanghai: Shanghai Kexue Jishu Chubanshe, 1990), 15.

[5] Geremie R. Barmé, “Mao Zedong’s West Lake: The Revolutionary Retreats Liu Villa 劉莊 and Wang Villa 汪莊,” accessed October 11, 2017, http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?searchterm=028_villa.inc&issue=028.

[6] Bai Linmiao 白林淼, Mao Jianxing 茅建興, and Zou Li 鄒麗. “Hangzhou dazao ‘dongfang rineiwa’ [ 杭州打造「東方日內瓦」Hangzhou Constructs the ‘Geneva

of the East’] . ” Wenhuipo (Hong Kong), January 30, 2010, accessed September 14, 2017, http://paper.wenweipo.com/2010/01/30/CH1001300015.htm.

[7] James Z Gao, The Communist Takeover of Hangzhou: The Transformation of City and Cadre, 1949-1954 (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2006), 218-221.

[8] Zhejiang sheng jiben jianshe dou pi gai lianluozhan deng, Zalan “dongfang rineiwa,” 1-3.

[9] In this way, the plan not only survived but to some extent predicted the Sino-Soviet Split.

[10] As a matter of fact, Hangzhou Xihu State Guesthouse, in which the Xi-Obama meeting on the eve of the 2016 G20 summit took place, is exactly where China and the U.S. reached the historic agreement in 1972. On September 3, 2016, the same day of the Xi-Obama meeting, the U.S. and China jointly announced that they formally ratified the Paris climate change agreement.

Lyu Yuan is the project director of the "Geneva of the East" Research Group in Hangzhou. He was also born and grew up in that city. Lyu is currently a graduate student at Institute of Chinese Studies, University of Freiburg, and was an exchange student at Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo in the fall semester 2017.