People who conduct research on English manuscript collections will be immediately familiar with names like Parker, Ashmole, Hunter, Bodley, Sloane or Cotton. It is very evident that we have the antiquarian interests of these long dead white males in wigs and/or frilly collars, who stare at us from portraits and statues, to thank for the survival of much of our cultural heritage. But who were people such as Archbishop Matthew Parker, Elias Ashmole, William Hunter, Thomas Bodley, Hans Sloane or Robert Cotton? What did antiquaries of the past use their manuscripts for? What were their personal reasons and motives for collecting them?

Sir Robert Bruce Cotton (1571-1631) assembled a famous library, which became one of the founding collections of the British Library. I’ve been working through his manuscripts in my attempt to identify and describe all English prose written between 1200 and 1500 contained within the collection. Here are my impressions.

.jpg)

A Portrait of Sir Robert Bruce Cotton, Baronet (image credit: James Tookey, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

What personally surprised me was how much of a historian Cotton was. I had first heard of the collection in connection with Beowulf and how the Old English heroic poem got damaged in a library fire. Gradually, I became aware of more famous manuscripts that were part of the collection (it helps that Cotton’s manuscripts are still known by the famous Roman emperor shelf marks, which are more memorable than most library shelf marks consisting of just letters and numbers) such as those containing Sir Gawain and the Green Knight or destroyed Old English works like the Battle of Maldon. If asked about why the collection is important and what is in it, I would have said Old English and named some literary works – but literary works are not the main focus of the collection.

Smith’s printed catalogue of 1696

We can get a more contemporary view of the significance of the collection from the first printed catalogue of it. This was written by the Reverend Thomas Smith and published in 1696 (pre-Cottonian fire). Smith was a scholar from Oxford, who worked as a librarian to Sir John Cotton, Sir Robert’s eldest grandson. He did not meet Robert Cotton in person, but his employer was 10 years old when his grandfather died, so there is something of a continuum and living memory extending to Sir Robert. Smith divides the material assembled by Cotton into six categories:

- Manuscripts written in the Anglo-Saxon tongue

- Cartularies of monasteries

- Lives and passions of saints and martyrs

- Genealogical tables

- Histories, annals and chronicles

- Original records of the kingdom

Since Smith listed Old English first, it seems that Smith and other contemporaries held Old English (which they call ‘Saxon’) in high regard. Smith has this to say about their survival:

“Nothing is known for certain as to where and from whom he obtained and redeemed, as it were, from wretched captivity those relics saved from the appalling destruction of houses of religion carried out under Henry VIII” (Smith, p. 46).

He describes the sad fate that they faced after the Reformation, noting the role of Archbishop Parker first:

“The rescue of a few planks from this fatal wreck seemed in his wisdom to Matthew Parker, archbishop of Canterbury, a man beyond all praise, to be a task worthy of the sacred position that he held in the Church of England. [...] But even after the grape-gathering of the reverend Matthew Parker many bunches still more plentiful were left to Cotton’s diligence to collect.” (Smith, pp. 47-48).

Archbishop Matthew Parker (image credit: Theodor de Bry, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

Matthew Parker (1504-1575) was the head of a rescue operation for Old English manuscripts, which was launched when he noticed that priceless manuscripts were being used as bungs for barrels or cloths for cleaning. His motives were also related to the reformation, as “historical or scriptural texts” could be used to “justify the position of the reformed English church by relating it to the early English church” (Rand, p. xx). In 1568, Parker was authorized by the Privy Council to collect ancient records, which he began to systematically search, employing several assistants and secretaries. Parker’s people drew lists of texts and authors considered important and approached people and institutions who owned them by sending letters, asking them to part with their manuscripts – which they did sometimes more, sometimes less willingly. Parker requisitioned the majority of his manuscripts from monastic houses, others were given as gifts and yet others were purchased.

Half a century later, in the time of Robert Cotton, who was four when Parker died, it would seem that manuscripts, including Old English ones, were circulating in antiquarian markets and were sought after artifacts. Cotton had connections not only in Britain but also with continental humanist scholars and antiquaries (such as the French historian Jacques Auguste du Thou, Isaac Casaubon and Nicolas Claude Fabri de Peiresc) and he was always on the lookout for new manuscripts. Like Parker, Cotton also received many as gifts. Sometimes he purchased entire libraries, when they came for on sale. For example, Cotton acquired eighty manuscripts from the library of Henry Sevile of Banke.

While Smith’s list shows that Old English was considered important, it is perhaps the other categories which give a better overview of the true strengths of the Cotton library. Categories 2 and 3 can perhaps be attributed to after-effects of the Reformation.

The ruins of Black Friars monastery, dissolved in the English Reformation by Henry VIII (image: Wikimedia Commons, Philip Halling / Black Friars Monastery).

The collection contains numerous monastic cartularies, annals and memoranda (including from St Peter’s Abbey in Westminster, Evesham Abbey, Hagnaby Abbey, the Priory of St Bartholomew in London and many others) and several saints’ lives – all of which must have been commonly in circulation after the dissolution of monasteries. Cotton also used monastic cartularies in his local history of Huntingdonshire (where he was from) and he seems to have been collecting manuscripts a for a large-scale ecclesiastical history of Britain even if the project never materialised. Demonstrating that the English church was historically independent of Rome was an important cause of the English reformation and had been a major driving aim of the scholarship of Matthew Parker.

Categories 4 to 6, however, seem to be the ones that were most central to Cotton’s own interests. Cotton had a really impressive collection of various chronicles and annals (including Bede, Gildas and Nennius, two copies of the Anglo-Saxon chronicle, a Brut chronicle, Robert Fabyan’s chronicle, Henry Knighton’s chronicle, a manuscript of the Polychronicon, several copies of the London chronicle), some genealogies, though he was not a herald, and a huge number original documents from the later Middle Ages to his own day, which Smith calls “original records of the kingdom”.

Cotton’s interest seems to have been in the history of his country from the distant past to his own day.

As Smith puts it:

“His purpose in this was not to make a grand showpiece of his collection or to earn applause in idle circles with amusing stories gathered from his reading or indulge his mind with useless and empty speculations, but to gain a thorough understanding of the whole shape of government in England traced in all its aspects and tasks from its earliest origin through successive centuries and supported by evidence collected by his powerful intelligence ...” (Smith, p. 30)

The Society of Antiquaries

As a young man Cotton was one of the founding members of the Society of Antiquaries – along with his Westminster teacher William Camden. The society would convene regularly and each of its members would research a topic and prepare a talk on it.

We can get an idea of the types of topics the society was interested in from the list of topics of their meetings given by Smith (p. 30):

- Of the antiquity of the laws of England

- Of the duel or single combat

- Of the antiquity of terms used in the administration of justice in the courts

- Of the antiquity of cities

- Of the dimensions of land among the English

- Of the antiquity and variety of measuring land in the county of Cornwall

- Of the variety of names by which this island was once known

- Of the antiquity of shires and when it was that England was first divided into them

- Of the antiquity, duties and privileges of heralds in England

- Of the antiquity and privileges of the houses or Inns of Court and Chancery

- Of knights made by abbots in the time of Henry I and earlier

- Of the antiquity of family coats of arms

- Of the antiquity and ceremonies of funerals

- Of the antiquity of towns, cities, castles and parishes

- Of the antiquity of military fiefs

- Of the antiquity and first origin of dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts, barons, knights, sergeants-at-law, esquires and others whom we call gentlemen

- Of epitaphs

- Of the antiquity, variety and principle of mottoes usually appended to coats of arms

- Of tenure, that is of the various ways of holding estates and lands

- Of seals

- Of sterling money, whence it got its name

- Of forests

- Of the division and boundaries of parishes

- Of tombs and other monuments intended to preserve the memory of the dead for posterity

- Of the antiquity of the palatine counties, honours and manors

- Of the antiquity of the Christian religion in Britain

- Of the antiquity, dignity and office or duty of the constable, marshal and seneschal of England.

Some of the contributions written by Cotton and his fellow antiquaries survive as leaflets bound in the manuscripts, sometimes as several on the same subject matter.

The sources assembled by Cotton reflect his interests. When researching a topic Cotton assembled numerous primary documents related to the topic. Many of the state papers contained in his collection are collected into large volumes, which focus on a certain theme and in which the documents themselves are compiled chronologically.

Moreover, like other antiquaries of the times he also often disassembled medieval manuscripts and rearranged them according to his own needs. As Sharpe (p. 69) puts it, “things were bound together that were consulted together”. This practice is different from modern bibliographical requirements and is bound to irritate scholars working with manuscripts that passed through the hands of Cotton, Sloane and their ilk. You can sense the frustration from Neil Ker’s comment:

“The mere numbers show that Cotton acquired considerably more manuscripts containing Anglo-Saxon than even Parker ever had. [...] As a collector he had tiresome habits. He separated manuscripts which belonged together and directed his binder to put unrelated manuscripts within the same cover. Everything he had seems to have been rebound by him.” (Ker, p. liv)

Perhaps the reason Cotton’s library was so central to intellectual life of his day came down to his friendly and helpful nature and good connections. Cotton seems to have enjoyed constant visitors to his library and was also happy to lend his books. Access to many other libraries was much more cumbersome (Sharpe, 73-74). The Bodleian library was mainly for members of the university, even if the keeper occasionally admitted outsiders, if they paid. Similarly, Parker’s manuscripts were in Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, which was somewhat difficult to get access to. Public records at the time were almost impossible to use. Cotton, on the other hand, seems always to have been happy to help.

“For every cause could [in Cotton’s library] find a weapon, each professional troop could therein marshal its ranks and frame its tactics. Most important, therein was to be found the body of experience of which all could partake in the fight against fortune and time for the building of a better future” (Sharpe, pp. 76-77, paraphrasing praise for Cotton’s library by Edmund Bolton).

Cotton’s political career

Cotton also had a fairly successful political career, in which he served as a Member of Parliament for several terms. In 1622, he bought a house in Westminster, after which his library was right next door to Parliament. Cotton let both the Commons and the Lords use his garden during parliamentary breaks.

Cotton’s political career and antiquarian interests were not separate from each other. Historical scholarship was linked to political concerns of the day. The Society of Antiquaries approached the ageing Elizabeth I, making a petition to the Queen to establish a national library for England. In doing so they cited two precedents in which the consultation of historical documents had proven essential. The first was when Edward I made all monasteries in England search for documents that proved English overlordship over Scotland. The second was the case Henry VIII made for being independent of papal jurisdiction. For unknown reasons, the ageing Queen turned the request down and the Society of Antiquaries was abolished.

Cotton seems to have had a good working relationship with James I, who often relied on his help and library for finding precedents on policies. On one occasion, he found historical precedents for why debasing coinage was not likely to work. Cotton also helped James I with a pet project, providing documentary sources for the French historian De Thun for writing a recent European history which would give a more positive portrayal of Mary Queen of Scots (the King’s mother) to combat a highly critical and hostile account by George Buchanan.

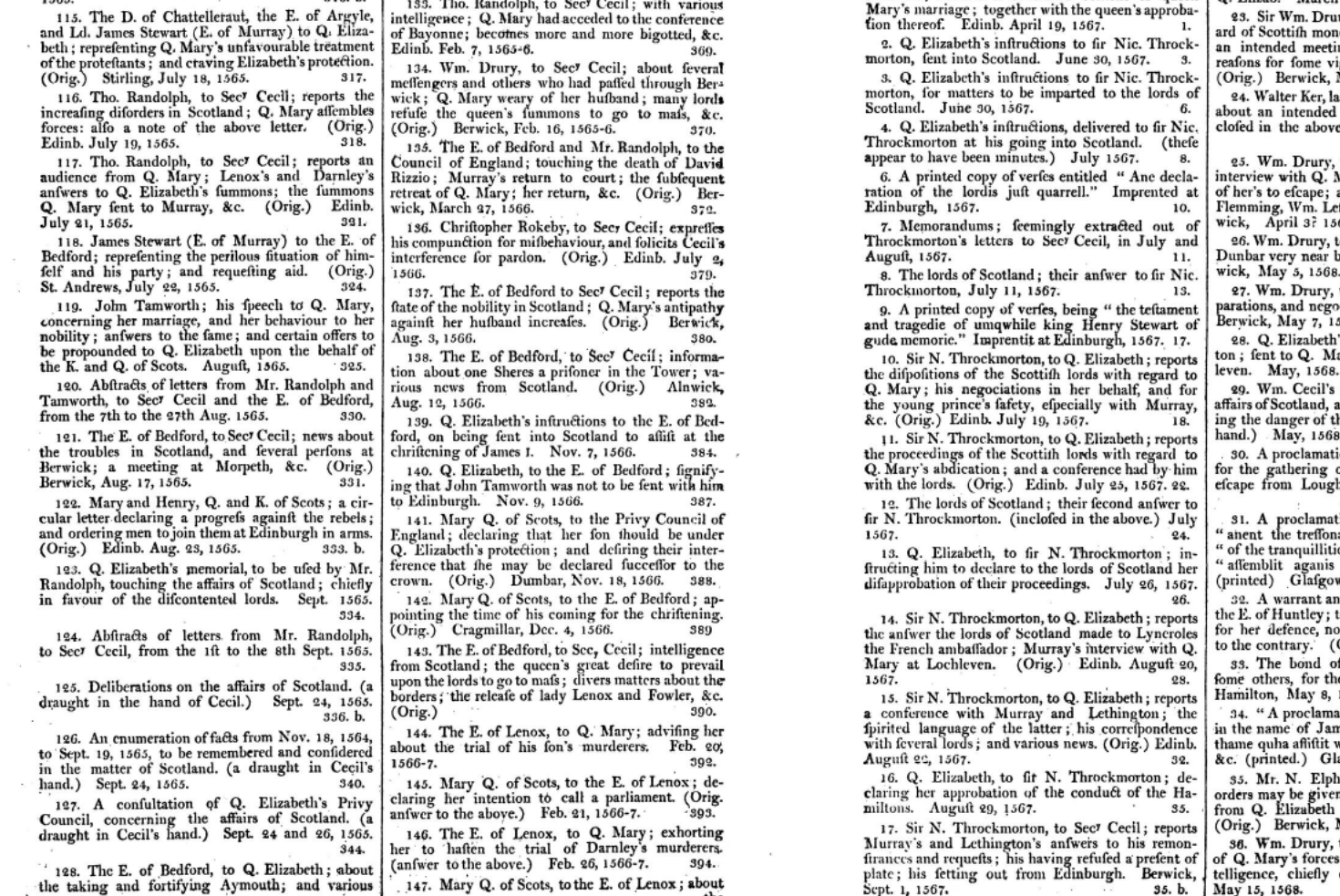

Some of the correspondence between Mary Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I in Cotton MS Caligula C I as described by Joseph Planta (1802: 88-89) in his A Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Cottonian Library Deposited in the British Museum. There are dozens of pages like this related to Mary in Planta's catalogue.

Cotton’s library even seemed to function as something of an unofficial state archive for Jacobean England. The list of people who made use of it is reminiscent of a who’s who at the time, from the king and the queen to Francis Bacon, to the playwright Ben Jonson (who was a close friend and is known to have spent the plague year 1603 at Cotton’s countryside estate in Connington), the anatomist William Harvey and many others.

Cotton’s royal favour, however, did not last to the reign of Charles I. He made enemies with the King and his favourite, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham. It was at this point the ability to use the library to find precedents became dangerous, and Cotton found himself on the parliamentarian side against the King, even though he did not live to see the Civil War. Cotton’s library was closed by Royal Order in 1630, an action that may have contributed to Cotton’s death in 1631 at the age of 61.

Sources:

Ker, N. R. 1957. Catalogue of Manuscripts Containing Anglo-Saxon. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Prescott, Andrew. 1997. “‘Their Present Miserable State of Cremation’: the Restoration of the Cotton Library” Sir Robert Cotton as a Collector: Essays on an Early Stuart Courtier and His Legacy, ed. By C. J. Wright. London: British Library Publications.

Rand, Kari Anne. 2009. The Index of Middle English Prose, Handlist XX: Manuscripts in the Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer.

Sharpe, Kevin. 1979 [2002]. Sir Robert Cotton 1586-1631: History and Politics in Early Modern England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, Thomas. 1696 [1984]. Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Cottonian Library (Catalogus librorum manuscriptorum bibliothecae Cottonianae). Reprinted from Sir Robert Harley’s copy, annotated by Humfrey Wanley, together with documents relating to the fire of 1731. Ed. C. G. C. Tite. Suffolk, 1696[1984].

You can read a scan of Smith’s catalogue here: (Catalogus librorum manuscriptorum Bibliothecae Cottonianae. Cui praemittuntur viri, d. Roberti Cottoni ... vita et Bibliothecae Cottonianae historia & synopsis. Scriptore Thoma Smitho .. : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive). The quotes are from a 1984 edition of Smith’s catalogue, which contains translations of the essays to modern English.

Tite, Colin G. C. 2003. The Early Records of Sir Robert Cotton’s Library: Formation, Cataloguing, Use. London: British Library.

.jpg)